(From Istoriya Leib-Gvardii Yegerskago polka za sto let 1796-1896, Chapter VIII. St. Petersburg, 1896.)

The Life-Guards Jäger Regiment.

Gadzhi-Gassan-Lar and the War of 1828 Against the Turks.

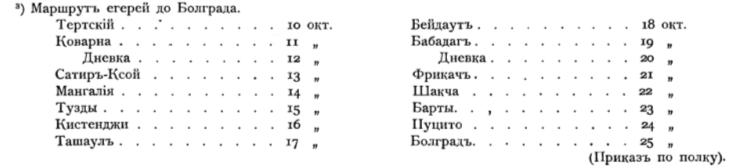

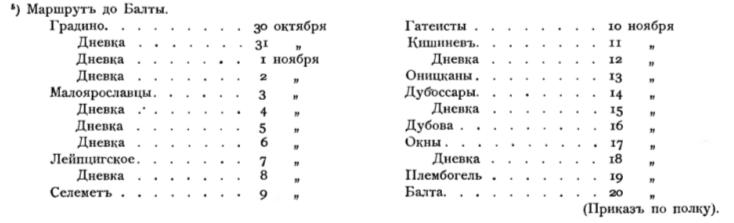

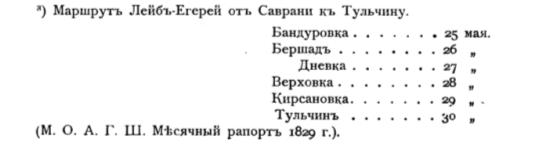

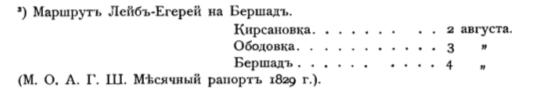

Reasons for the war. - The regiment marches out on campaign 5 April 1828. - March to Bulgaria. - Siege of Varna. - Affair at Gadzhi-Gassan-Lar 10 September 1828. - Formation of the 2nd Battalion from personnel of the 13th and 14th Jäger Companies. - Battle of 16 September. - Operations at Varna in the second half of September and the surrender of the fortress. - Departure for Russia 10 October. - Halt in the Balta area during the winter of 1828-1829. - Camp at Tulchin. - New flag for the 2nd Battalion. - Return to St. Petersburg February 1830.

The Porte’s continual violations of the 1812 Treaty of Bucharest and 1826 Akkerman Convention led to Russia and England declaring that further infractions would result in a joint fleet being sent out against the Turks. The Porte dismissed this threat and on 8 October of the same year the Turkish and Egyptian fleets were destroyed at Navarino. The allies’ success did not subdue Turkey’s attitude and the sultan issued a declaration calling the faithful to war against Russia. As he saw that all measures taken to preserve peace were fruitless, Emperor Nicholas I was forced to announce to his own people in a manifesto of 14 April 1828 a final severance of relations and a state of war with Turkey.1

At the end of 1827 the 2nd Army, deployed against the Turkish border, had already been ordered to be ready to march. It was reinforced from the 1st Army by the 3rd Infantry Corps, 4th Reserve Cavalry Corps, Bug Lancer Division, and 10th Infantry Division.2 Later this army was joined by the 2nd Infantry Division and Guards Corps. At the beginning of military operations the 2nd Army’s total strength was about 113,000 men.3

General Field-Marshal Graf Wittgenstein was named commander-in-chief of all forces operating in European Turkey. The emperor approved a plan for military operations in which upon arrival at the Danube one part of the field army was designated for besieging fortresses and a second part for securing the occupied territory and guarding communications.4

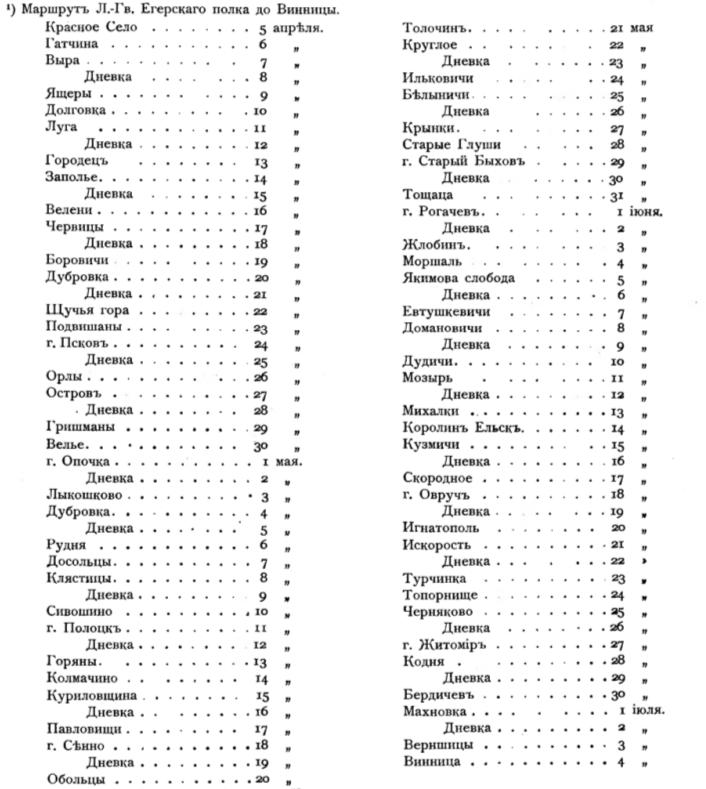

On 28 February 1828 a Highest Order was sent to Grand Duke Michael Pavlovich to prepare the Guards Corps for campaign.5 Active preparations in our regiment began immediately. The 1st and 2nd Battalions were designated for the campaign, and shortfalls in manpower were made up by personnel from the 3rd Battalion.6 Additionally, when on the march the regiment was to be joined by one hundred men selected from army jäger regiments. The Guards Corps was divided into two columns, and each column was organized into eight sections. The L.-Gds. Jäger Regiment made up the third section of the right column, commanded by General-Adjutant Bistrom.7 On 5 April, the day designated for departure, the jägers heard prayer services in their barracks, said farewell to the 3rd Battalion that was being left behind, and set off to link up with the L.-Gds. Semenovskii Regiment. At 10 o’clock in the morning the Emperor Nicholas Pavlovich arrived with the empresses Alexandra Theodorovna and Maria Theodorovna, accompanied by foreign princes and a numerous suite. After inspection by the tsar the jägers made a ceremonial march past Their Majesties along the middle boulevard of the Semenovskii district, and the regiment left the city through the Narva gates, accompanied by the tsar’s best wishes.8 On 5 April 1828 the regiment set off with the following strength: 1 general, 3 field-grade officers, 11 company-grade officers, 160 non-commissioned officers, 94 musicians, and 1560 privates.9 Behind the regiment came the train of officers’ goods and a government wagon train in the order and sequence prescribed for campaigning. The government wagon train consisted of 15 wagons with 41 horses (eight ammunition carriages drawn by 3 horses, 1 apothecary wagon drawn by 4 horses, 1 paymaster wagon with 2 horses, 4 medical carts with 2 horses, 1 tool wagon with 3 horses).10 In addition the regiment was followed by a detachment from the 1st Train Battalion consisting of 1 non-commissioned officer, 21 privates, 12 supply wagons, and 1 mobile field smithy, commanded by a company-grade officer.11

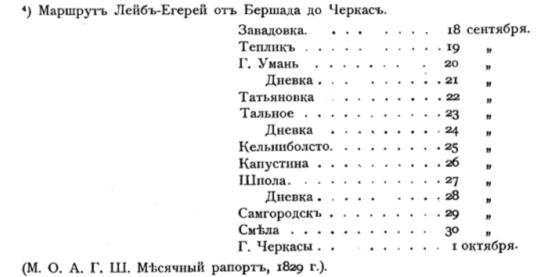

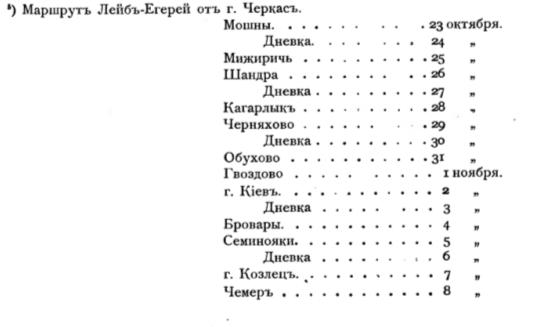

According to the given route of march, the L.-Gds. Jäger Regiment was to pass through Gdov, Narva, Pskov, and on to Tulchin where the entire Guards Corps was to be united. Overflowing rivers made the right column’s proposed route completely impassable up to Pskov, so it was ordered to go to the village of Borovichi along with the left column and from there to Pskov and beyond.12 On 6 April the jägers arrived in Gatchina where the dowager empress gave the officers a farewill dinner along with bread and salt in the old Russian custom.13

During the march rest days were frequent and distances moderate so that the men remained almost entirely fresh. The farther we went from St. Petersburg the drier the roads became, which made the marches much easier. In regard to provisions the regiment was well taken care of. At the route’s rest stops the war ministry had arranged for provisions and forage. The regiment sent out two detachments of bakers a day’s march ahead so that for the whole journey the guards jägers had fresh bread. The regiment mostly moved by companies, and only in some of the towns were the battalions united, or even the entire regiment. In those instances the ranks with the band playing passed through in front of one or another high commander. The march stages were monotonous in the extreme and only variances in quartering arrangements provided some interest. Typically, early each morning the general march was beaten, signaling the companies to form up and move out. Halfway through the march a halt was made, during which time the train would catch up to the companies and then hurry onward on its own to the night halt to prepare dinner. Several miles before the place the regimental headquarters was to be located quartering officers would appear and direct the companies to their lodgings. On the second half of each day’s march, after the halt, the men would pass through villages and settlements with singers in front, which lifted the soldier’s spirits and drove away fatigue. In Polotsk, where the Leib-Jägers arrived on 11 May, they were joined by 74 men selected from army jäger regiments as reinforcements.

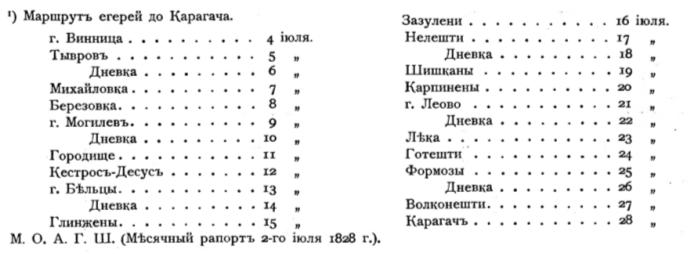

From Vinnitsa the jägers were ordered to go not to Tulchin but directly to the Danube. Because of the great heat marches were made at night. The men were in good spirits up to the halt, but afterwards it was hard to go on as the usual hour for sleep came and it took great effort to fight off drowsiness. Up to Karagach the regiment continued to march by companies and be dispersed among villages, but from 28 July it began to make encampments as a body, using tents brought up by camp trains.14 From Karagach the jägers went to Satunov and came up to the Danube, which was crossed by a bridge of boats. On the Turkish side they deployed near the fortress of Isakchi. Here the two columns from the Guards Corps united and stayed ten days while preparing for further movments.15 The following arrangements were made for the Guards’ entry into Bulgaria: 1) regiments were to have rations for 4 days and forage for 5; 2) lower ranks were to be issued 3 meat and 2 spirits portions each week; 3) company-grade officers were authorized to each receive a pound of meat a day and a soldier’s rations, while field-grade officers were given double rations.16

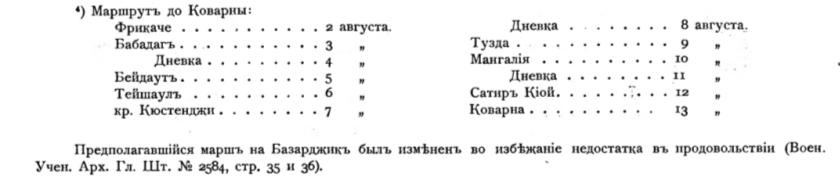

From Isakchi the Guards Corps moved in four echelons: the first echelon, including the L.-Gds. Jäger Regiment, left for Kovarna on 2 August.17 The road to Kovarna was very unpleasant. Along its sides were scattered the carcasses of dead cows, making the air unbearable; the villages wee burnt out and looted; a few times bands of wandering Bulgars were encountered. The terrible heat made the marches very difficult. At the halts the sun made the ground so hot one could not sit down. To ease the soldier’s condition Grand Duke Michael Pavlovich ordered that neckcloths be taken off, collars be opened, and canteens be hung on sword hilts so that at any opportunity the soldiers could scoop up water. It was forbidden to drink the water untreated in these regions because it was unhealthy—vinegar or vodka had to be added to it.18 The jägers reached Kovarna on 13 August and stayed here until the 24th, the day designated for setting off for Varna by the jäger brigade, which together with the L.-Gds. Black-Sea Squadron and Light Company No. 2 made up the Guards Corps vanguard.19

The road to Varna passed through defiles and forests and was strewn with rocks that not only hindered the train but the infantry as well. Previous rains finally made it impassable and the men had to pull the greater part of the guns and wagons by hand. However, this did not slow the jägers’ march and on 26 August they reached Varna as scheduled by Grand Duke Michael Pavlovich.

Before continuing with the Leib-Jägers’ part in the 1828 campaign, we will say a few words about the circumstances preceding the Guards Corps’ arrival at the fortess of Varna. The Russian army designated for operations had crossed the Prut River on 25 April and the Danube on 27 June at Isakchi in the presence of the emperor.

Although military operations following the crossing had been favorable for us, they were greatly slowed by campaign difficulties in a waterless and sparsely populated country. Long wagon trains and a huge number of sick hampered the movements of troops so it was decided to use the sea to ease communications with Russia and therefor occupy the coastal fortress of Constanța. The army took it on 12 June and moved toward Shumla. However, it soon became clear that our forces were not enough to capture such an unapproachable fortress, and the commander-in-chief was forced to leave small detachments to keep Shumla under observation and while turning the main body of troops to the coastal fortress of Varna.

The fortress of Varna lies on the coast of the Black Sea at the mouth of the small Devno stream which widened westwards of Varna to form a lagoon or liman of the same name. To the south in front of the fortress the stream again narrowed considerably and in this form flowed into the Black Sea. Varna lies on the north bank of the Devno. South of this stream, about 8 miles away, flows the Kamchik, almost parallel to the Devno lagoon before reaching the sea. On its north side the fortress is surrounded by hills at some distance beyond a cannon shot. On the west these hills approached closer to the walls; gardens and vinyards were surrounded by stone walls and therefore were convenient for defense. From the south the fortress was protected by a marsh. Therefor Varna could be attacked only from the north.

Varna was an important strategic point because it covered one of the main roads across the Balkans to Constantinople. In 1828 its fortifications consisted of a main wall with 14 earthen bastions. Almost all of them were connected by curtain walls for small arms. On the seaward side the fortress was protected by a stone wall with loopholes. It contained an arsenal that was a large citadel suitable for defense with small arms.

Russian naval control of the Black Sea appeared to be a important prerequisite for a successful siege of this first-class strongpoint because it would serve to safeguard Russian operational lines and the transport of necessary supplies.

On 28 June a force of 4500 men was sent to Varna under the command of General-Adjutant Graf Sukhtelen 2, with orders to seal up the fortress and thus protect the army’s main line of communications in that direction, and also make contact with a Russian squadron expected to arrive at Varna. Graf Sukhtelen approached Varna from the north and dispersed a Turkish cavalry force of some 8000 men. On 1 July he took up a defensive possession at the distance of a second parallel from the fortress wall with his right flank on the Devno lagoon and his left on gardens and heights. His small force stood here until 6 July and with impressive steadiness fought off several sorties by the Varna garrions, which by 4 July had already increased to 12,000 men.

On the night of 6 July Sukhtelen was relieved in his position in front of Varna by General Lieutenant Ushakov, who had at his command no more than 1300 men. Sukhtelen saw that this small detachment was inadequate in the face of the fortress’s large garrison and decided to leave with Ushakov some 1200 men from his own command. He then left with his remaining troops for Pravody in accordance with his orders. On the following day, having confirmed the small size of the Russian force, the Turks resolved to destroy it. However, thanks to excellent placement of field fortifications in the position and the timely sending by Graf Sukhtelen of one battalion and two squadrons with two guns requested as reinforcements, General Ushakov on 8 July repulsed fierce attacks on his position for over 17 hours and forced the enemy to withdraw into the fortress works despite outnumbering the Russians several times over. Fearful that the Turks would use their numbers to come around his rearin spite of his success in the fighting, General Ushakov on that same night ordered an immediate withdrawal from his position to Dervent-Kioi, 8 miles from Varna on the road to Pravody. Here he deployed his detachment in battle formation on the heights and stood here until 19 July.

On 20 July Vice-Admiral Prince Menshikov arrived. He had been given command over all troops at Varna, now grown to 10,000 men. After a skirmish with an enemy force of 2000, on 22 July Prince Menshikov occupied a position at the village Franki and established communications with the Russian fleet. He relied on it to close Varna from the sea from the north side to the liman, and he strengthened his own position by building a chain of redoubts that secured it from the constant sorties of the garrison which numbered over 15,000 men. In regard to the south side of the fortress, a shortage of troops forced Prince Menshikov to limit himself to observing enemy activities. Siege works were begun on 1 August, with the northeast sector chosen for the attack as it offered the possibility of cooperation with the Black Sea squadron during siege operations.

During a Turkish sortie on 9 August Prince Menshikov was seriously wounded in both legs and could no longer personally command the siege. His chief of staff, Major General Perovskii, continued operations according to the prince’s known intentions and followed his directions. In accordance with a Highest Order, on 18 August the governor-general of New Russia and Bessarabia, Graf Vorontsov, took over command of the besieging troops. He fully approved the plan of attack and the placements of siege works. Under his direction the siege was energetically continued and by 21 August a second parallel was laid, and despite the Turks’ brave resistance approaches were brought up to the glacis. Nevertheless we were unable to achieve any decisive successes because our lack of troops made it impossible to surround the fortress on all sides and thus cut off the reinforcements and supplies from over the Balkans and even from the fortified Turkish encampment at Shumla. For these reasons, when the Guards Corps arrived at Varna a special force under General-Adjutant Golovin was organized to invest the fortress from the south side. The Life-Guards Jäger and Finland regiments were part of this force along with other troops, and its total strength was about 6500 men.20

During the night of 29-30 August the Leib-Jägers received orders to prepare to advance. Briefings were hurriedly done. A quantity of supplies and equipment was piled up at the tents along with the sick, who were being left here, and the jägers took with them only a few changes of underclothes, a second pair of boots, and some other necessities.21

The column left camp on 30 August and on that same night reached the village of Gebedzhi where Major General Akinf’ev’s vanguard was located, it being designated to join General-Adjutant Golovin’s force. Here we spent the night under the open sky since the troops had not taken tents with them as they expected to encounter the enemy on Varna’s south side and because the hilly terrain made the route difficult. They only had ammunition boxes, medical carts, and the barest minimum of pack animals. After a long halt, at 8 o’clock on the following morning they proceeded further around Varna in battle formation.22 The entire march was along a narrow road through thick forest. The column spread out in a long file which seriously slowed down movement.23 At about 2 o’clock in the afternoon we came out into a small field opposite the village of Gadzhi-Gassan-Lar and there made a halt. Before evening, and not yet having reached the place where the roads to Burgas and Pravody cross, the vanguard took the wrong direction due to a guide’s mistake. They had to turn back in order to come out onto the road to the Varna heights. This movement was accompanied by great difficulties since the main force was spread out behind the vanguard along a road so narrow that the march formation was limited to three abreast. It was already rather late when by chance we found a kind of hollow in the woods which could just barely contain the force. The column’s tail was against the woods, and the head was only some yards from the forest on the other side.24 A reconnaissance could not be undertaken because of darkness, and after the column made some dinner it laid down for the night. A surrounding chain of infantry outposts, a line of mounted vedettes, and patrols sent out on the roads provided security from sudden attack. In case of an alarm the men were under orders to stand to arms and not move from place. The night proceeded quietly and at dawn on 31 August we moved on.25 Now the path immediately became almost impassable at more frequent intervals. Finally, the way ahead appeared to open up—villages became less frequent and the jägers came out onto hilly terrain with a sparse sprinkling of hamlets, with woods again alternating with open hills. At last, they descended from a large flat plateau into a valley, again made their way onto a similar large tableland, reached the edge of a hillside... and in front of troops stood Varna.26 Three cannon shots were fired to signal the arrival of the column.

After a short rest General-Adjutant Golovin personally undertook an inspection of the foot of the mountain and plain in front of Varna, for which he took the 6th Company of the Life-Guards Jäger Regiment and a squadron of the Bug Lancer Regiment. This small force proved to be adequate to not only keep the terrain under observation, but also to clear it of the enemy, during which a number of Turks were taken prisoner.27 After carrying out the reconnaissance, Golovin detached the 19th Jäger Regiment and two squadrons of the Bug Lancers with two light guns to occupy the base of the uplands. Command of the force was given to General Akinf’ev, who set up posts in a line from the sea to the liman.

The remaining troops were drawn up in battle formation on the slopes, and in the rear of the main force a strong picquet was established to observe the routes leading from the Balkans. The next day Golovin found it necessary to deploy an observation force facing toward the Kamchik. The Kamchik River was insignificant but fairly deep and swift in places, and was about 15 miles to the south of Varna in the Balkan mountains.28 Having designated a line to drawn up on and chosen four points that were immediately occupied by the Life-Guards Jäger Regiment divided into four half-battalions, Golovin ordered redoubts to be built at those places. On this day the Turks made a small sortie. Our artillery quickly forced them back. Afterwards Golovin issued orders that designated four more new points for redoubts. Having thus strengthened his position, he sent a battalion from the Duke of Wellington’s Infantry Regiment and two companies of the Life-Guards Finland Regiment to reinforce Akinf’ev.29

It was known that a separate corps of troops under Pasha Omer-Vrioni was coming to Varna from Shumla with the intent of breaking through to the fortress and forcing us to lift the siege. This news put the southern force in a very dangerous situation. It was completely cut off from Graf Vorontsov’s forces and had no way to retreat, since on one side lay the sea and on the other the liman, while in the rear was the fortress. It could not receive speedy reinforcement except by ships. Foreseeing this need, a wharf was built on the shore near the Galaty-Burun cape, and a company of the Guards Équipage was placed there, arriving on 31 August. In spite of the alarming rumours of Omer-Vrioni’s proximity, Emperor Nicholas I set off on 5 September for General Golovin’s column. The sovereign inspected the position in detail and conversed with men in each company. He approved Golovin’s arrangements and personally designated a location for building a flèche. He then returned to the wharf to sail to the fleet.30

When places were chosen for fortifications, the infantry was used to help the sappers build redoubts. Wagons were circled at some distance behind the redoubts, and within them were placed all government and officers’ supplies and the sutlers. Here also lay the sick until they could be sent to Varna's north side . Battalions were located behind the redoubts in attack column formation. To get relief from the heat, the soldiers made shaded shelters from branches, while officers had huts built from poles and branches, of which there was no shortage. In regard to provisions Golovin’s force was fully supplied thanks to the Galaty wharf and foraging, which was frequently resorted to due to lack of animal fodder. In the first days of September the Leib-Jägers were fully rested from the long march and even began to feel bored from lack of activity. Officers often walked the three miles from the position to Captain Kromin’s forward post. He had been sent there on 2 September with his 2nd Company of Leib-Jägers and a platoon of lancers, to the junction of the roads from Pravody and beyond the Kamchik.

While

the Leib-Jägers

continued to peacefully stand on the south side of Varna, Golovin

took measures to strengthen his position. Until 8 September the

Turks hardly showed themselves. Only

on 3 September was a report received from Colonel Lazich about the

appearance of a superior enemy forces, and then on the 8th Captain

Kromin reported that a party of 25 jägers and

6 lancers under Ensign Vasil’ev had run into 30 Turks in an unnamed

village on the road to Pravody. The Turks were chased into the woods

and Ensign Vasil’ev returned with two prisoners. The enemy’s

appearance placed Kromin’s detachment in danger so he was ordered

to return to the encampment.31 Early

in the morning of the next day, all the column’s foragers were

gathered together in the vanguard. Since the previous day’s report

gave reason to suppose an encounter with the enemy would be possible,

the 3rd Company of the L.-Gds Jäger Regiment,

two platoons of the L.-Gds. Finland Regiment, and a platoon of

lancers, were all placed under the command of the 3rd Company’s commander,

Captain Kruze. The column of Captain Kruze and the foragers arrived at the village of Akendzhi

unopposed. The needed number of foragers was organized and

provided with pack horses. They then moved back in the following

order: 1 platoon of infantry in the lead, 2 in the middle, and a

fourth in the at the rear of the column. The cavalry was divided up

and placed between platoons. Mounted and foot patrols moved along

both sides. While marching in this way along a narrow road, the

foragers were attacked by Turkish cavalry between the head of the

column and its center. This attack was unsuccessful because firing

from our patrols greatly weakened the assault’s determination. Upon

hearing the shots, the platoon covering the head of the column halted

and thus gave some of the foragers an opportunity to pass by (most of

them abandoned their forage). Other platoons hurried to join the

front of the column. At this time the Turks again made an attack and

were able to get between elements of the covering infantry, but the

platoons in the vanguard and rear guard successfully used their

bayonets to force their way through crowds of enemy soldiers and

reach the head platoon. The Captain Kruze continued onward in closed

ranks in spite of all the Turks’ efforts, and safely brought his

force into camp at 7 in the evening, having inflicted significant

harm on the enemy with his firing. In all the covering force suffered

7 killed or missing and 5 wounded. Although the foraging expedition

did not have the desired results, the fight against a much stronger

enemy ended in our favor. Captain Kruze, Sub-Lieutenant Tilicheev,

and Sub-Lieuteant Demidov of the Life-Guards Finland Regiment, by their coolness in the

midst of great danger were able to keep order in

their units. Some of the young soldiers, having seen the enemy for

the first time, brought into the camp weapons and clothing of the

Turks they had run through during the fighting.32

This

affair caused us to be more careful when sending out foragers. The lack

of forage became more and more pressing, so a new foraging expedition

was proposed for 10 September to the village of Akendzhi, but covered

by a battalion of the L.-Gds. Jäger Regiment

and two squadrons of horse jägers with

two guns from the Don cossack artillery. Since the 1st Carabinier

Company of the L.-Gds Jäger Regiment under Staff-Captain Engelhardt had been on that day sent at dawn to

reconnoiter the strength of an enemy force whose cavalry had appeared

on the heights near the village of Mimisaflar, its place was taken by

the 1st Jäger Company

of the L.-Gds. Finland Regiment under Captain Nasakin.33

Meanwhile main headquarters again received information on the movement of

Omer-Vrioni’s corps. The emperor had been on board the Parizh

since 27 August and consequently a Highest Order was sent by

telegraph from the ship to immediately send a sufficiently strong

force to reconnoiter the approaching enemy. Command was to be given

to a colonel in the Polish forces, Aide-de-Camp

Graf Załuski, who had several days before been assigned to

General-Adjutant Golovin’s column.34

That choice proved to be fatal. He was unfamiliar with the soldiers entrusted to him as well as the

broken and wooded terrain in which the enemy was advancing and which

demanded extreme care in moving troops. Colonel Załuski ignored all

advice and by his neglect, not to say other defects, caused the

destruction of a significant part of the Life-Guards Jäger Regiment.35 The

proposed foraging expedition was canceled and the already prepared

regiment found out about its new mission from the following words to

the Leib-Jägers by their commander, Major General Gartong: The column marched out at 11:30 AM

on the road normally used by foragers. Załuski sent part of his

cossacks forward to patrol the road and kept the rest with himself as

a covering force. The troops had hardly descended the heights into a

defile when Staff-Captain Engelhardt emerged from the left, not

having sighted the enemy anywhere. He was directed to return to the

place he had come from and remain there until further orders. Soon

a cossack galloped up and reported that there was a Turkish picquet

in the clearing (previously occupied by Kromin), and that upon

sighting the cossacks fired shots and galloped off. It was then

explained to Załuski that when infantry was on the move it generally

put out a vanguard, especially when in wooded terrain. As a

vanguard the 1st Battalion’s 6th Platoon was called forward under

Ensign Stepanov. The cossacks were withdrawn, and patrols were sent

out from the vanguard.

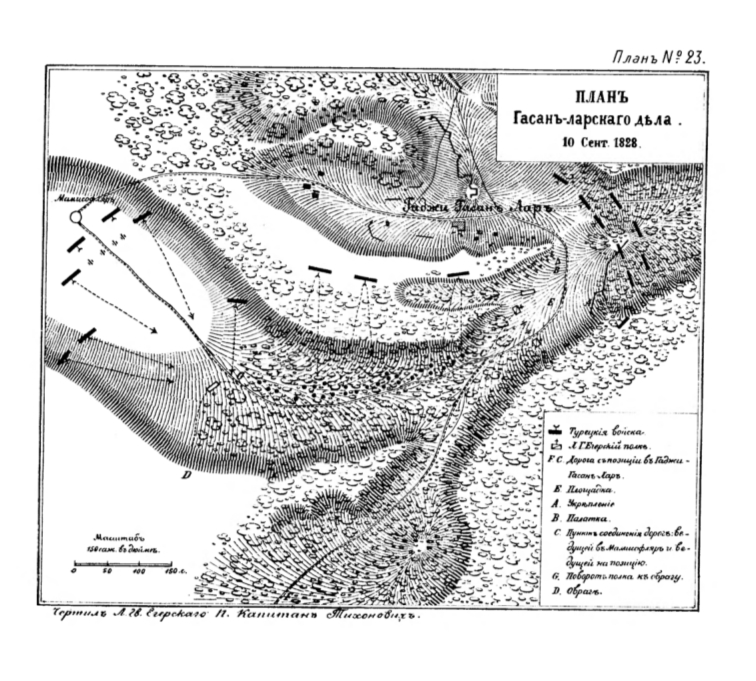

Continuing

forward, the 6th Platoon came across a naked corpse lying sideways

across the road at the place where the foragers had been attacked the

previous day. The body had been savagely cut up. Suddenly shots were

heard ahead. Non-Commissioned Officer Ignatii Mikhailov came running

from his patrol to tell Stepanov that Turks were hidden in the bushes

along the road. Encouraging his men, Stepanov ordered them not to

fire, but upon seeing the enemy to rush on them with the bayonet.

They had not managed to go a hundred paces when from the woods on the

left and right firing blazed forth and they were showered with

bullets. As one, the jägers

threw themselves forward with the bayonet. The Turks ran with the

jägers following them, and on their heels they came out into an bright

clearing (E) (plan No. 23). Upon coming out of the woods the platoon

gathered together and formed up in the clearing to the right of the

road in expectation of the regiment. The opening which they had come

to was about 500 paces long but very narrow, especially at the exit

from the forest. On the right it was bordered by low shrubs, and on

the left by a vinyard. Straight ahead on a hill was a sparse woods of

tall trees. In this woods were the Turks, who became agitated when

they saw the Russian soldiers. It was obvious that they had been

taken unaware and were trying to form up. Variously colored cloaks

flashed between the trees. Horsemen galloped in different directions.

At first it seemed that they were small in number, but then the

entire half circle in front of the jägers

became filled with a multitude of Turks.

Opposite

them on the right at about 100 paces was a house or lodge (A) from

which turbaned heads poked out. On the left, about 200 paces away,

stood a green tent (B). Soon the battalions came up: The 1st went to

the left and the 2nd to the right, in columns of attack. Two guns

were placed between the battalions. The open clearing was so confined

that the 1st Battalion’s left flank jutted into the vinyard while

the 2nd’s right was in the bushes. The cavalry stood in front of

the 1st Battalion’s left flank facing the vinyard. Graf Załuski

appeared behind the infantry. As soon as he saw the masses of Turks,

he ordered the cossacks who formed his escort to withdraw, saying

that their colorful dress would serve as a target for the enemy. When

the regiment was formed up it had not been ordered what to do next. It was

apparent that the Turks totaled over 10,000 men. Colonels Sarger and

Busse were convinced they could overthrow the Turks and strongly

demanded permission to immediately hit them and then return by the

same road. If the Turks came around them from behind, they would

fight their way through to fords not far away. But Graf Załuski

objected to this, saying that the purpose of the reconnaissance was

not a battle but information about the enemy, so the mission was

completed and now it was time to go back.

The execution of Graf

Załuski’s decision began with the cavalry making

their way by files back into the woods. The artillery fired some

solid shot and explosive shell into the woods and canister on the

entrenchments. During this time the Turks themselves extended to the

right and left around our flanks. Marksmen from the 2nd Battalion

were summoned into the bushes and from the 1st—into the vinyard.

Behind the horse jägers moved the L.-Gds. Finland Regiment’s 1st Company, then the

artillery and its covering escort—the 2nd Battalion’s 6th Platoon

under Tilicheev, and lastly the 3rd Company with Captain Kruze.

Załuski left with this group following the road leading back to

camp, and charged General Gartong to hold on for a while and then

withdraw. In

this way 700 Leib-Jägers without artillery were left facing an enemy over ten times stronger

and already encouraged by our retreat. Gartong asked Załuski to

leave the artillery with him but he refused, saying the loss of a few

men was not a bad thing but loss of guns would be a dishonor that he

did not want to risk. From Załuski’s actions it is clear that he

was only concerned about saving himself. He did not even think about

the fact that in the woods, cut up by a multitude of roads, it would

be easy to lose the way, and he did not care about maintaining

contact with the regiment, as he did not put out vedettes as guides

at crossroads. When

Załuski was in the woods he saw some road to the left and

ordered Ensign Stepanov to go there with his platoon, and when asked

by the latter, “Where to?” he answered, “To where it leads!”

Soon Stepanov’s platoon came out onto a big road, but while he was

going along it Turkish voices were clearly heard from behind

impenetrable vegetation in the woods. Załuski’s escort was perhaps

half a mile from the regiment when already heavy firing broke out

behind them. This so alarmed him that he ordered Captain Kruze to

increase the pace to a run. But Kruze explained that such a pace was

inappropriate for a Russian soldier during a withdrawal, and in spite

of all Załuski’s insistence continued to march at a normal walk.

When they came to the elevated clearing previously occupied by

Kromin, the group halted. From here Mimisaflar was visible, around

which a firefight was ongoing. No one could figure out how the

Leib-Jägers

managed to get over there. The most plausible explanation was that

the jäger regiment

had defeated the Turks and were driving them to the Kamchik. Soon

this conclusion was greatly undermined by the appearance of a much

wounded non-commissioned officer from the 2nd Battalion who told how

the regiment had been cut up, that the regimental commander had been

killed near him, and that in retreat the jägers

lost the right road. After staying a short time in the clearing,

Załuski moved toward our position.

After

Graf Załuski moved out with his group, General-Adjutant Golovin remained without

any information from him for several hours. Only at about 4

o’clock in the afternoon did a private from the Seversk Horse-Jäger Regiment

gallop up with the news that the L.-Gds. Jäger Regiment

was surrounded on all sides and in extreme danger. This appeared to be

so unbelievable that it was not given any importance. Soon a note in

French came from Załuski containing the following: “I encountered

the enemy in large numbers. The situation and location were very bad.

General Gartong with his entire regiment remained in the rearguard.

Apparently the enemy halted, but Your Excellency might report by the

telegraph that I came in contact with the enemy in superior numbers.”

At

the same time wounded soldiers of the L.-Gds. Jäger Regiment

began to come in. Some of them maintained that the regiment was

conducting a fighting withdrawal, others confirmed the initial

information, adding that the regiment was completely destroyed. After

Graf Załuski’s first report Ensign Kinovich of the L.-Gds. Finland

Regiment came from him to General-Adjutant Golovin with an oral message “that the entire column is retiring in order, but the L.-Gds. Jäger Regiment,

forming the rearguard, is a little behind due to skirmishing having

broken out with the enemy.” This last information appeared to be more

plausible. Meanwhile the number of wounded jägers

grew. They arrived singly, without arms, and all confirmed the dreadful

news of the regiment’s annihilation and the loss of their commander

and all officers. In expectation of further information they

were all gathered into a vanguard. Finally, Graf Załuski’s group

appeared, and as it approached the position he galloped ahead to

General Golovin who stood in alarmed expectation at the base of the

Kurtepe mountain, and reported to him orally: that the entire column

was retreating in order, that he brought all the cavalry with himself

along with the artillery and five infantry platoons; that the

remaining part of the L.-Gds. Jäger Regiment

at the tail of the column was covering the withdrawal under the

command of General Gartong, that this rearguard was not far off but

could not arrive together with him only because it was engaged in

skirmishing with the enemy; however, the withdrawal was being

conducted in good order, and nothing unfortunate had happened.

After listening to this report,

General-Adjutant Golovin pointed out to Załuski that as commander of

the column he should remain with the rearguard, especially since it

was actually engaged with the enemy. Graf Załuski countered that he

considered his presence more needed with the cavalry and artillery,

all the more so since the guards jägers

had their regimental commander himself with them and there was no

reason to risk any kind of confusion. He followed this with relating

what preceded his retreat. Golovin was listening and unable to

understand why wounded jägers

continued to come in singly with all unanimously maintaining that the

regiment was destroyed, that they themselves saw their leaders

killed, and when themselves wounded they barely managed to reach the position.

Załuski, though, kept on insisting that the regiment was retreating

in an orderly manner. At this time their emerged from the woods a horse and rider lead by a cossack

holding the bridle. It was the regimental paymaster,

Lieutenant Gen 2, without his shako and covered in blood.

“Gen,” cried Golovin, “where did you leave the regiment?”

“The regiment is no more.”

“What are you saying? That cannot be!”

“At first we retired in order, but they killed the general, they killed Sarger, they shot everyone. There were too many of the Turks, they

overwhelmed us... Maybe I am the only one left now.”

“How many Turks do you think there were?”

“I don’t know, but surely at least twenty thousand.”

“Eyes grow wide in fear,” pointed out Załuski.

“Yes,” countered Gen angrily, “we saw you, Colonel, when you came out onto the field where the Turkish host was!...”

Golovin cut Gen off, “You are feverish, go to the aid post immediately.” Gen had six wounds.

In spite of the eyewitness

testimony from Gen which was confirmed by what the arriving soldiers

were saying, Golovin apparently did not believe him, or rather, did

not want to believe him. The platoon of jägers under

Ensign Stepanov that had returned to the position as Graf Załuski’s

escort was immediately sent to meet the regiment. This platoon

covered about two or three miles without meeting anyone. Not knowing

what else to do, Stepanov ordered the drummer to beat the rally in

the hope that jägers

wandering in the woods would come out. Only the 1st Carabinier

Company answered the muster, having been last ordered by Graf Załuski

to await his directions. Its commander, Staff-Captain Engelhardt,

knew nothing of the regiment’s fate and only heard the firing

around the village of Mimisaflar. A number of Turks were moving

toward the sound of shooting but then stood the whole day facing his

company, probably taking it for a vanguard of a larger force. It was already completely

dark when Stepanov returned to the position. To General-Adjutant Golovin who

was waiting for him he reported that except for the 1st Carabinier

Company he had met no one. Thus there remained no doubt as to the

disaster that had overtaken the Leib-Jägers:

not one element of the regiment returned whole.

During

the night wounded soldiers continued to find their way in, including

the commander of the 2nd Battalion Colonel Uvarov, Captain

Rostovtsov, Sub-Lieutenant Ignat’ev 2 (wounded), and Ensigns Gerard

and Zagoskin. From the testimony of the returned officers and lower

ranks details emerged about the destruction of the L.-Gds. Jäger Regiment.

Hardly had the artillery left the clearing in which the

Leib-Jägers stood, and Graf Załuski started his withdrawal, when heavy firing started up between the

Turks and the marksmen deployed on the regiment’s right and left

flanks. Enemy infantry then attacked the marksmen

and cavalry charged the regiment’s front. The frontal attack was

beaten off by the battalions’ volley fire, but

the marksmen were all massacred with four officers perishing:

Lieutenant Nesterov and Ensigns Divov, Vasil’ev, and Skul’skii.

The pressure from the Turks on the right was so strong that they

pushed in the right face and thus broke the square. The 2nd

Carabinier Company moved forward to repulse the Turks and Colonel

Gartong restored order. Seeing the complete impossibility of holding

out against such a numerous enemy he decided to begin a

withdrawalto use the few free minutes following the attack that had just been beaten off. Having turned the battalions to face the rear he

commanded, “Half-turn, right!”... This was his last command.

Hardly had he said it when a bullet struck him dead from his horse.

General P. A. Stepanov in his notes calls this command unfortunate

because it led the regiment to its annihilation. Gartong, being in

the 2nd Battalions’s square, commanded “Half-turn, right!”

because the road lay to the right of that unit. The regiment,

however, took it to mean the direction for further movement. Marching

thusly, the jägers reached the corner (C) where the roads forked. The lead personnel

went along the road to the right (C.G.) and behind them followed the

whole regiment. Behind the retreating regiment came the Turks. They

came so close that the rear platoons had to turn around and step

backwards while firing. During this skirmishing Lieutenant Aprelev

was killed. Soon not even retreat could save the regiment: it was surrounded by Turks

hidden in the thick vegetation who picked off the passing jägers

at will. In the confusion no one thought in time to send out

skirmishers, and then it became impossible to do so on a road

completely occupied by a narrow and tightly packed column in which

the leaders could not personally impose any kind of order between the

head and tail. Shouts of command were swallowed by the firing and

cries from the wounded. At each crossroads, in all the hollows, there

appeared fresh masses of Turks who had to be fought through with the

bayonet, with the enemy behind constantly growing stronger. Moving

slowly and with difficulty, lossing many men killed and wounded, the

jägers came out into a rather wide, treeless space that sloped upwards and

in which was a village. Only here was the mistake in direction

discovered. Those who had been on the foraging expedition recognized

the village of Mimisaflar which was seven miles from General

Golovin’s position. The crushing blow of this realization was

increased by the sight of fresh Turkish forces across the the

roadway. It was later revealed that on this day the L.-Gds. Jäger Regiment

had run into the 30,000 strong Turkish corps commanded by Pasha Omer-Vrioni.

Black - Turkish forces; White - L.Gds. Jägers; FC - Road from the Russian main position to Gadzhi-Gasan-Lar; E - Clearing; A - Fortification; B - Tent: C - Where roads join that lead to Mimisaflar and to the main position; G - Turning of the regiment to the ravine; D - Ravine.

The

debouchment of the jägers from the woods was met by enemy artillery fire. Using the delay

caused by our men having to reorganize by battalion (during the march

through the woods the companies had become mixed up), the Turks moved

infantry and cavalry up to attack. The

cavalry struck the 2nd Battalion which was in the rear and succeeded

in cutting off its tail end. The band of jägers

which had fallen into such a hopeless situation fought desparately.

The first to fall here was Colonel Busse. He defended himself for a

long time with musket in hand until a bullet struck him down and a

Turkish officer took off his head with his saber... Seeing that

defeat was inevitable, some of our officers decided to destroy the

2nd Battalion flag they had with them so that it would not fall into

the hands of the Turks. Captain Kromin, Lieutenant Sabanin, and

Sub-Lieutenant Skvanchi tore the cloth from the staff, divided it

into three parts and hid them under their clothes. The broke the

staff into pieces and buried the eagle in the ground. They had just

managed to do this when Kromin and Skvanchi were killed and Sabanin,

wounded in the thigh and side, was taken prisoner. Here also were

captured Captain Ignat’ev, Staff-Captain

Aleksandr Rostovtsov, Lieutenant Sukin, Ensign Mokrinskii, and Junker Officer

Candidates Rachinskii and Dokhturov, all wounded, and 70 lower ranks,

of whom only four were not wounded.

The details of the fate of the 2nd Battalion’s flag, considered lost for 47 years, were only revealed in 1875 after the death of Nikolai

Aleksandrovich Sabanin. Taken

prisoner, he guarded this regimental relic made sacred by the blood

of his predecessors and stained with his own. He told none of his

companions in captivity of his secret, fearing that from resulting

talk the Turks might somehow find out about it. When he returned from

captivity in 1829 he still did not tell anyone about the flag’s

fate. Only when he was dying did he enjoin his wife to send the flag

to the emperor. Why Sabanin hid this is very much a mystery. In the

regiment’s miserable condition, the saving of a flag through effort

and dedication was something that would find full approval from

anyone who held the regiment’s honor dear. Therefore modesty alone

cannot explain Sabanin’s failure to present the flag pieces he had

preserved, when that flag was being sought after even in

Constantinople. Apparently he was guided by other reasons. We know

that all the circumstances of the unfortunate affair at

Gadzhi-Gassan-Lar greatly saddened the sovereign and for a long time

afterwards any mention of this event was difficult for him. The

sovereign, who throughout the siege of Varna did not interfere in the

commanding generals’ arrangements and only followed the course of

the overall siege plan, in this had case personally named Colonel

Załuski to command the reconnaissance that had such a sad result for

the glorious L.-Gds. Jäger Regiment.

This was apparently known to Sabanin and

upon his return from captivity again kept him from bringing up an

affair that was already beginning to be forgotten. Having not promptly turned

over the flag fragments he had saved, it is possible that

Sabanin did not do so later from fear of being held responsible for

not having done so earlier, and so kept his secret until death.

Finally, his decision may have been influenced by the fact that the

lost St.-George flag has already been replaced by a new one. After

the fall of Varna the sovereign granted St.-George flags to the

13th and 14th Jäger Regiments

with the inscription “For distinction at the siege and capture of

Anapa and Varna 1828,” and the same kind of flag was given to the

2nd Battalion of the L.-Gds. Jäger Regiment

whose ranks were refilled by personnel from the above mentioned

regiments. The recovered flag thus had no place and Sabanin may have

thought that this piece of material drenched in his own blood

would be turned in to some old arsenal. In any case, on 5 August 1875

Lieutenant-General Petr Aleksandrovich Stepanov joyfully presented

Emperor Alexander II the 2nd Battalion’s flag saved by Sabanin.39

On 17 August of that same year, on the regimental birthday, this

remnant was ceremoniously carried in the emperor’s presence to the

L.-Gds. Jäger Regiment’s chapel, where it had been ordered to be kept.

Let

us return to the interrupted account of the regiment’s destruction.

While the rearguard was being annihilated by greatly

superior enemy numbers as described, the leading part of the regiment continued to

move forward slowly, firing all the while. When it came to a deep

ravine (G) overgrown to the edges with thick woods, the jägers

did not think long before hurrying into it, hoping to find cover from

the Turks. But here the greater part of them perished. A dense wall

of Turks occupied the edges of the ravine and shot the remnants of

the regiment to pieces, primarily directing their fire at the black

frockcoats of the officers. Here were killed Staff-Captain Zhilin 1

and Lieutenant Gen 1. Colonel Sarger

encouraged his soldiers by his personal example, clambering up the steep opposite side of the

ravine and shouting to them, “Don’t falter, boys! Fire back!”

But with these words he fell lifeless from his horse. The battalion

adjutant who was with him, Ensign Gerard, halted, took a small icon

from around his neck, raised it over his head and cried, “To me,

boys! God will protect us!” A group of jägers

gathered around him, all men who were completely worn out and for the

most part wounded. No longer followed by the Turks, but hardly able to move their legs,

they made their way through the forest to our position, only arriving at

nightfall. Along the way they were joined by wounded and unwounded

men. Many did not make it to the position but died along the road.

Among them was Sub-Lieutenant Lebyadnikov, whose body was found in

the bushes not far from camp.

The Leib-Jägers lost 14 officers killed that day: regimental commander Major General Gartong, Colonels Flügel-Adjutant

Sarger and Busse, Captain Kromin, Staff-Captain Zhilin 1; Lieutenants

Gen 1, Aprelev, and Sukin; Sub-Lieutenants Skvanchi, Nesterov, and

Lebyadnikov; Ensigns Vasil’ev, Skul’skii, and Divov,40

and 358 lower ranks.41

Four officers captured: Staff-Captain Ignat’ev; Lieutenants Rostovtsov and Sabanin; Ensign Mokrinskii,42

and 82 lower ranks.43

Only 5 officers and 256 lower ranks returned from the reconnaissance,

of whom 2 officers and over half the men were wounded.

From the details of the affair of Gadzhi-Gassan-Lar as just related above, we see that the destruction of the regiment was the result of two main

reasons:

2) No

communication between the retreating vanguard and rearguard, which

Graf Załuski did not see necessary to establish, being distracted by saving the cavalry, artillery,

and perhaps something else even more precious to him. A consequence of these reasons was a third—taking the wrong direction during the withdrawal. Instead of getting closer to hour position,

the jägers gradually moved further away and were marching toward an enemy significantly

superior in numbers.

Details of

the regiment’s defeat only became known much later, and in the

first days the only known facts were the destruction of the regiment and the loss of the flag and almost all officers, which was reported

to the sovereign. It is easy to imagine Emperor Nicholas I’s

anger at the regiment which had been unable to fulfill the hopes

placed on it. Under the influence of the crushing news he wrote to

Graf Diebitsch a letter containing the following:

Ship

Parizh, 11 September

I have nothing good to relate to you this time, dear friend. Yesterday

evening something unbelievable and shameful happened in Golovin’s

command. Previously we had intelligence of the enemy coming near our

foragers who nevertheless made their escape like fine fellows and

even brought back with them horses taken from the Turks. Yesterday

morning I ordered Golovin: “Send Colonel Załuski

with a strong party to reconnoiter the enemy.” Golovin formed a

column of two squadrons of my jägers,

2 Don guns, and the Guards Jäger

Regiment. This large force, by no means a “party,” set off with

Załuski and Gartong, who

asked to go with the regiment. At 2 o’clock in the afternoon, eight

miles from camp, they came onto the Turkish army camp. The Jäger

Regiment’s first reaction was to attack them, but Załuski

stopped the jägers and

started firing with his cannons, which is to say he made things worse

when it would have been better to do nothing. The Turks had been so

taken by surprise the their horses were still not saddled, and they

then started to exchange fire. Then Załuski,

finding himself too weak to attack them, ordered the regiment to

withdraw, and himself took away the horse jägers

and both guns. Thus he was first to appear back in camp having

abandoned his infantry. Then the jägers

were apparently seized by panic! So one way or another 800 men in all

with 11 officers and Colonel Uvarov returned. The rest were taken

prisoner, killed, or scattered. All the other officers were killed or

went missing. Another two more officers returned, one of which had

four bullet wounds, and 103 wounded lower ranks. In regard to the

rest we know nothing. They say that Gartong, Sarger, and Busse were

killed. It’s terrible and unbelievable! I immediately sent Bistrom to

take charge, conduct an inquiry, and put the regiment back in order.

He just reported to me that he is taking responsibility for the

regiment and will keep it at his position, and that the Turks

appeared to be drawing toward the liman, perhaps with the intent of

falling on the right wing and on that side forcing their way into the

town. I am sending an order to the 19th Division—if they are

already on the road—to go straight to Devno, and for Dellingshausen

to move to Gebedzhi as soon as the division arrives. I also ordered

that the Guards cavalry arrive by this evening so that we are

sufficiently strong. But it will necessarily be required that when

the 19th Division arrives in place, it moves from Devno to Kamchik in

order that we have better contact between our forces. This movement

can be supported from here along the sea coast. The siege is

progressing forward. The forward bastions are already in our hands,

and the descent into the trench and second breach are almost

finished. Still the Turks resist stubbornly so I cannot say how this

business will end. Dear friend, my heart is broken from this sad event

that I do not understand. Yours always N. There is no rusk, but lots

of oats. My respects to the field marshal The following Highest Order was sent to Grand Duke Michael Pavlovich, commanding the Guards Corps: 1) All field and company-grade officers and lower ranks of the L.-Gds. Jäger Regiment who were in the affair of 10 September are to be immediately expelled from the regiment, transferring officers and lower ranks, the former in their present ranks, to army line regiments;

2) His Imperial Highness’s Company, the 3rd jäger Company, and the

6th Platoon of the 2nd Battalion, which did not take part in this

affair, including officers, as well as lower ranks who were not

present due to sickness, being on detached duties, or other reasons,

are all to be combined to form the 1st Battalion of the L.-Gds. Jäger Regiment;

3) Field and company-grade officers and all lower ranks of the 13th and 14th jäger Regiments now at the sieges of Anapa and Varna are

designated to form the 2nd Battalion of the L.-Gds. Jäger Regiment,—after the successful end of the sieges of these fortresses. At dawn on 11 September the tired jägers were gotten up due to the arrival at the position of the commander of the infantry of the

Guards Corps, General-Adjutant Bistrom. He had been ordered to carry

out an investigation into the affair of Gadzhi-Gassan-Lar. The men

who had come back from the massacre were formed up separately from

those who had not taken part. Officers were also brought together

here. K. I. Bistrom sternly surveyed the remnants of the regiment,

numbering 130 men, and without the customary salutations quietly said

to them, “This is what has pleased the Sovereign Emperor to write

to me: henceforth the name L.-Gds. Jäger Regiment ‘is

abolished...’” Ensign Stepanov was a witness to this miserable

scene and described it thusly: “I did not hear anything of what

followed. My thoughts went numb and I did not understand the words

that I heard. I recovered myself only when Karl Ivanovich began to

shout. Turning to those who had been in the battle, he said, “You

have shamed yourselves, jägers, shamed yourselves! My twenty years

of glory are gone! Where did you put the flag which I earned for you

with my wounds? Where is your general? Where are your leaders? Why

did you return without them? Why didn’t you remain there with them?

You don’t have enough blood to redeem that which they shed...” At

this moment Ensign Gerard, still almost just a boy, stepped out of

the ranks and said loudly, “Your Excellency, you have been given

false reports! We fought as hard as we could. One can’t fight

against twenty. We didn’t run. Out of the whole regiment the only

ones left are those you see before you. All the rest fell.” Karl

Ivanovich excused Gerard for his breach of protocol and said to him,

“Gerard, you come to me afterward when I call for you.”45

That same day 1 field-grade officer, 3 company-grade officers, 13 non-commissioned officers,46

12 musicians, and 175 privates—in all 204 jägers who had returned

from the battle—were sent to the north side of Varna and attached

to the 13th and 14th jäger Regiments for operations in the

trenches.47

The

losses suffered by the L.-Gds. Jäger Regiment gave

rise to a supposition that the Turks, encouraged by their success,

would act more boldly against Golovin’s column, so on the night of

11 September the force was reinforced by the L.-Gds. Pavlovsk

Regiment. This measure appeared to be all the more necessary because

it had become known that the Turks intended to break through to the

fortress. In such circumstances the division of the southern column

into a blockade force and an upper defensive force made it absolutely

necessary that there be experienced commanders for both groups. K. I.

Bistrom was named commander of the southern column as a whole. He

inspected the position occupied by Golovin and judged it entirely

appropriate for defense. To strengthen the position even more, he had

two new redoubts raised and protected the upper position with five

more.48

Bistrom also made a few alterations in the troop deployments, so the

remnants of the L.-Gd. Jäger Regiment which had been in the main

position behind the redoubts and flèche

in attack column formation were moved to a large hollow between our

position and the Kurtepe heights, in order to serve as a reserve to

the cavalry which was maintaining vedettes on that mountain. Graf

Załuski commanded all the advance posts and

made his quarters near our battalion. Naturally this close proximity

was very unpleasant for the jägers. In Załuski they rightly saw the

cause of all the misfortunes that had overtaken them: his thoughtless

dispositions led the regiment to destruction,49

the lost of its flag, and above all—because of him the regiment

incurred the scorn and anger of their Sovereign.

Hatred

of Załuski grew even more after a rumor spread through the position

that he had written a letter to the tsar in which he justified his

actions by saying that the jägers lacked courage and had become

frightened. In truth, he had managed to convince everyone that the

Jäger Regiment had brought shame upon itself. That this opinion was

widespread may be judged from the following words of the eyewitness

Stepanov:

During

the night of 12 to 13 September the jägers who had been sent to

Varna’s north side and to occupy trenches with the 13th and

14th Jäger Regiments took a more than active role in an attack on

the Turkish camp on our position’s right flank about 600 yards from

the fortress.The jägers marched at the head of the column under

Colonel Prince Prozorovskii and bravely rushed the fortifications

covering the camp. They drove out the Turks at the point of the

bayonet and cleared the area for volunteers from the Nizovsk,

Mogilev, and Duke of Wellington’s regiments who were following

behind them. Supported by the 1st Battalion of the L.-Gds.

Semenovskii Regiment these took possession of the fortifications.51

The jägers’ coolness and undaunted courage in this action showed

all that if they fought here with the old jäger spirit then they

must have also done so on the 10th. The only difference was that on

that day they were almost all laid low but this time they only lost two

jägers.52

The jägers’ trophy on this day was a Turkish flag taken by Private

Istomin of the 5th Jäger Company (now 7th).53

This affair greatly softened general opinions. It’s been said that

Yakov Ivanovich Rostovtsov expended much effort to ensure Grand

Duke Michael Pavlovich interceded with the sovereign on behalf of the

jägers.

In

the meantime all was quiet on Varna’s south side. A platoon under

Ensign Stepanov was sent out to reconnoiter on 13 September and

returned to report that Turkish forces were gathering around

Mimisaflara in preparation of some sort of operation. As it turned

out, after midday the Turks occupied all of the Kurtepe heights and

set out a picquet line in front. Our vedettes were forced to move

back and the Leib-Jägers withdrew to the main position to the

depression which they had occupied up to now and set out a line of

sentries. Our composite battalion was busy this whole day with

building lodgements around the wagon circle. During the night the 1st

Carabinier Company went out as the sentry line.54

The next day was spent in a harmless exchange of fire at no clear

targets. The Turks tried to push back our line but were quickly

beaten off by Staff-Captain Engelhardt who led his platoon forward

with fixed bayonets. By evening the firing ceased.

Early

on the morning of 15 September Colonel Baron Fredericks, aide-de-camp

to the tsar, came to the jägers, having been named to command the

battalion. The jägers were cheered by his arrival because

Frederiks’ appearance in their ranks showed that the sovereign did

not consider them disgraced because otherwise he would not have put his personal

aide-de-camp in a jäger uniform. The colonel observed the

battalion’s dispositions and then left, but soon returned with orders

from General-Adjutant Bistrom to send out in front one platoon which

if necessary was to attack with the bayonet any Turks coming close to

our picquet line. During this time the main part of Omar-Vrioni’s

forces were observing the Russian position. Ensign Stepanov was sent

to carry out the orders as received, and he halted his platoon on the

crest of a hill.55

Soon Baron Fredericks approached the platoon and ordered it to

advance. The platoon moved forward just in time because the

approaching Turks were pushing back the horse jägers. The jägers

passed through the cavalry picquet line and continued onward in spite

of the hellish fire directed at them. Seeing that their firing was

not stopping them, the Turks scurried back. The entire area in front

of the jägers was cleared of the enemy, but suddenly Ensign Stepanov

noticed a Turk lying in the bushes, taking aim at the commander. He

said to him, “Colonel! They are aiming at you!”

“Let

them,” answered Fredericks.

“They

are close. He’ll hit you.”

“He’ll

miss.”

“Allow

me to chase him away with a volley from the flank.”

“It’s

not worth the powder.”

In

spite of that answer, Stepanov ordered the first rank to fire and in

that manner saved his new commander. Having cleared the area for

skirmishers, the jägers returned. But hardly had they left when the

Turks again started to press forward. Fredericks then ordered that

ten of the best marksmen be chosen and sent to reinforce the line.

The accurate firing of these select men forced the Turks to withdraw

and seek cover. Having in this manner saved the skirmishers from

short-range enemy fire, the marksmen continued lying down behind the

crest of a small hill. Around evening time the battalion occupied

Redoubt No. 4.

Tsar

Nicholas Pavlovich carefully followed the progress of the siege of

Varna. He supposed from the dispositions given

to him in Shumla on 16 September that

Prince Eugene of Württemberg

would certainly join up with General-Adjutant Sukhozanet (commander

of the special column observing the Turks’ movements) and on that

same day attack Omer-Vrioni, and so he ordered General Bistrom with

his column to support that attack. As a result of receiving those

orders, on the 16th the troops of General Bistrom were in full

readiness for battle, only awaiting the arranged signal.56

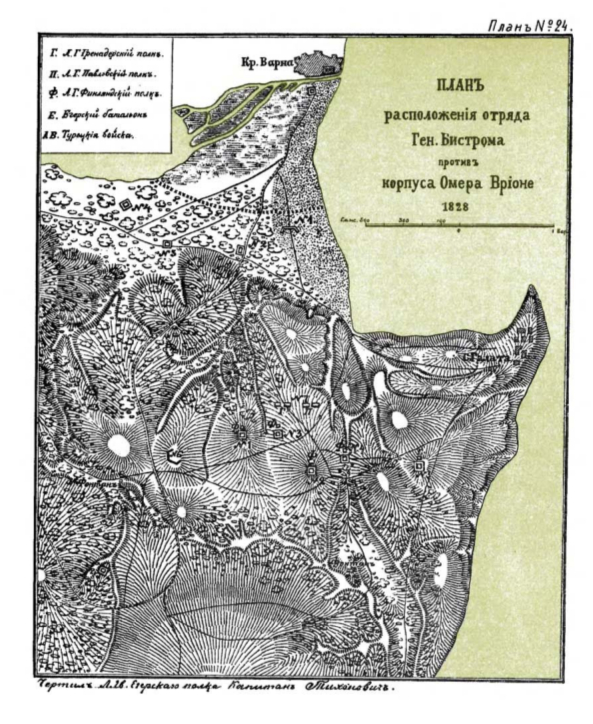

In the morning the jägers were led from Redoubt No. 4 and the 1st

Carabinier Company occupied Redoubt No. 1, the 3rd Composite

Company—Redoubt No. 2 (where

Bistrom was located), the 2nd Composite Company—Redoubt No. 3, and

the 4th Composite Company stood between Redoubt No. 4 and the L.-Gds.

Grenadier Regiment, protecting the position’s left flank, closer to

the sea (Plan No. 24).

G - L.-Gds. Grenadiers; P - L.-Gds. Pavlovsk; F - L.-Gds. Finland; E - Jäger battalion; AB - Turkish forces Soon

significant movement was noticed among the Turks. They opened

artillery fire and then moved to the attack. Accurate fire from our

guns in the redoubts did not stop the advance of the Turkish columns.

They closed up the gaps created in their ranks on the march and

continued their movement forward, in this way coming towards us to

within canister range. Riddled by canister fire, they were stopped,

but upon recovering themselves they again came on and reached a place

overgrown with bushes where they quickly dispersed and opened up

musket fire which we answered from breastworks and trenches. But

suddenly the Turks rose up and with a wild cry threw themselves into

the attack. They ran up so close that the jägers began to

make out their faces. At that moment the familiar call was heard:

“Jägers!”... Looking around, they saw Karl Ivanovich standing on

the breastwork.—“Jägers, forward!” he shouted. With

a joyous cry they answered their former commander and without firing

rose out of the trench. Met with a volley, they rushed at the Turks

at a run, and a mêlée ensued.

At the same time Staff-Captain Engelhardt came out of Redoubt No. 1 and

struck the Turks with one platoon while the other one in his

company was ordered to descend into the ravine that bordered our

position’s right flank. A

little before the attack on Redoubt No. 2 the Turks, primarily cavalry, had fallen on our

position’s left flank in great numbers where

the L.-Gds. Grenadier Regiment was defending. Seeing the press of the

enemy, Baron Fredericks hurried with the 4th Company to the

grenadiers’ aid. Opening fire, they contained the enemy, but

nevertheless the Turks carried out several desperate attacks. Formed

into a square, the grenadiers beat off all attacks and themselves

went over to the offense. During this their regimental commander

Major General Freitag was killed, as was battalion commander Colonel

Zaitsev. Aide-de-Camp Prince Meshcherskii rallied the halted

grenadiers and again led them into the attack. The battalion’s

decisive advance and its arrival in support of the L.-Gds. Pavlovsk

Regiment’s 1st Battalion put the Turks to flight. Some of them went

to their camp, and some moved along the ravine to join the attackers

on Redoubt No. 2.

When

the Turks were going past Redoubt No. 4, Ensign Nol’yanov with his

division jumped out of the redoubt, struck them in the flank, and

forced their way into the ravine.

On

our position’s right flank the Turks succeeded in

breaking through and coming around our rear in spite of fire

from Flèche No. 6 and resistance from the 1st Carabinier Company’s picquet line. Here

they attacked the wagon circle. Within the wagon circle there was no

one besides the wounded, orderlies, non-combatants, and a small naval

detachment. When the Turks began to climb out of the ravine, Captain

Ignat’ev’s driver, named Anan’ev, began to shout, “Grab

whatever you can, to march and hit the Turks!” Made up of personnel

variously armed with muskets, short swords, or lances, the group

rushed on the enemy with such speed that later some 300 dead and

wounded were counted around the wagons. Withering fire from the

L.-Gds. Finland Regiment’s 2nd Battalion decisively put an end to

any Turkish desire to attack our right flank. Meanwhile a sharp fight

was going on in front of Redoubt No. 2. Reinforced by fresh troops,

the Turks pressed forward more and more strongly. Several bravos

managed to jump onto our breastwork but there they fell. Kruze’s

platoon hurried up to support the exhausted 3rd Composite Company.

Together the jägers hit the enemy and forced him to run. In

this affair Captain Kruze57

and Privates Sipor and Belov seized a green Turkish flag.58

The

battle of 16 September lasted from 11 o’clock in the morning to 2

o’clock in the afternoon, during which the proposed joint Russian

movement did not take place and General Bistrom had to bear the

assault of 25,000 Turks by himself. He suffered very little

casualties and at the same time gloriously repulsed all the enemy’s

desperate attempts to break into our fortifications.59

On this day the

jägers lost 25 lower ranks killed and missing.60

After the end of the fighting K. I. Bistrom thanked the jägers and

said that they preserved the position. Naturally such flattering

gratitude raised the heavy spirits of the remains of the regiment. P.

A. Stepanov, a participant in this fight, wrote in his Notes: On

17 September the Turks were busy fortifying their position. On our

side a new redoubt was also built—No. 5, on the far left flank of

the position. On this day new reinforcements arrived: the 2nd

Battalion of the L.-Gds. Grenadier Regiment, six guns of L.-Gds.

Light Company No. 1, and six rocket stands of a light half-battery.62

At night a picquet line was put out by the Leib-Jägers’ 3rd

Company.That there

was a numerous enemy close by made us be as alert as possible: the

line was positioned in the bushes in the depression between the two

positions. There strict silence was observed; orders and challenges

were made in soft voices, signals were given by short whistles. Every

quarter hour patrols were sent out. In front of the line a listening

post was maintained the whole night, consisting of a non-commissioned

officer and three privates. In the morning the infantry picquets were

relieved by cavalry.63

Late at

night K. I. Bistrom held a military council to consider the attack on

the Turkish position scheduled for the following day. Emperor

Nicholas had been misled by an erroneous report from

General-Adjutant Sukhozanet that only 6000 men defended the Turkish

position and he ordered Bistrom and Prince Eugene of Württemberg

to simultaneously attack

Omer-Vrioni’s fortified Turkish camp on the 18th

from two sides. Bistrom and all members of the council were of the

opinion that the attack should be postponed, but they were not

listened to. In spite of all representations made as to the error of

Sukhozanet’s assessment of the size of the enemy force, no delays

were allowed. Leaving the tent, a vexed Bistrom drew Sukhozanet

aside and said to him, “Tell the Sovereign that I am read to go

into the assault with a musket in hand as a simple soldier, but I

will not take responsibility as a commander. You have false

information about the enemy and on your hands alone will be the blood

of the men who tomorrow will die for nothing.”64

Bistrom

had to attack the Turks from the front, and the Prince of Württemberg from the left flank

(since 15 September His Royal Highness’s column had occupied a

position at the village of Gadzhi-Gassan-Lar). A

special force under General-Adjutant Golovin was formed for the

attack on the Turkish camp. As part of this force the 1st Battalion of the

L.-Gds. Grenadier Regiment and the composite battalion of the

Leib-Jägers were ordered to seize a Turkish redoubt on the left

flank, while the remaining troops were to support

the attack.

At about

3 o’clock heavy firing was heard from the direction of Kurtepe,

evidence that the Prince of Württemberg was beginning his

advance.65

Bistrom’s frontal attack then started immediately. Firstly, the

Leib-Jägers and grenadiers marched in a single line. The Turks did

not fire on the advancing battalions at all until they came out onto

the plain, and only then began to shower them with shot, shell, and

canister. The jägers advanced in spite of the withering fire, boldly

marching forward. At this time they received an order to move to the

right and go along the road which cut up a gully onto the hill on

which stood the redoubt. The lead sections entered the gully, which

was blocked with abatis that they quickly dismantled while ignoring

the deadly fire from behind the branches. Then the redoubt

appeared a hundred paces in front of them. The jägers bravely

marched upon it, but the entire lead section was laid low, and with

them Ensign Nol’yanov was seriously wounded. Staff-Captain

Engelhardt with his carabinier company moved to the right, uphill,

and crossed a ditch to come into the redoubt’s flank. But at the

moment he reached the earthen wall a

Turkish bullet hit

him in the chest and he fell into the arms of his carabiniers, who

carried him away, already dead. Here too battalion commander

Aide-de-Camp Baron Fredericks was wounded in the knee while he was

moving forward to encourage the jägers. The battalion of

Leib-Grenadiers making their frontal attack was also repulsed, and

its commander Aide-de-Camp Prince Meshcherskii seriously wounded.

Despite failure and the loss of their senior leaders, both

battalions quickly reformed and again rushed into the attack but

were beaten back a second time.

Meanwhile

General Bistrom received word of the loss of the battalion commanders

and the death of Captain Vel’yaminov-Zernov of the General Staff,

who had been leading troops attacking the fortifications, so he

immediately sent his adjutant, Captain Mal’kovskii, to take command

and lead the troops into the assault.

Having

formed the men up, Mal’kovskii lead a third attack but was

critically wounded at its start. The battalions were unshaken by the

loss of their new commander and for a third time made a bayonet

attack but for a third time again repulsed.66

In view of the heavy casualties and the impossibility of taking a

redoubt protected by so much obstructive vegetation and a greatly

superior number of enemy troops, General Golovin ordered a

withdrawal. Several times Turkish cavalry tried to take the attacking

battalions in the flank, but each time they were beaten off with the

help of artillery and two battalions of the L.-Gds. Finland Regiment.

In this affair the jägers lost Staff-Captain Engelhardt and 45 lower

ranks killed,67

and Sub-Lieutenant Tizenhauzen,

Ensigns Nol’yanov, Tilicheev, and Lermantov, and 231 lower ranks

wounded.

The

chief of His Imperial Majesty’s Main Staff, Graf Diebitsch, was

with the force on that day and when the jägers returned to our

position he summoned Captain Kruze. “How

many of you are left?” he asked.

“Two

hundred and forty men,” answered Kruze.

“Tell

these heroes for me, that in my eyes they are worth a thousand men.”68

The

next day the jägers were ordered to occupy Redoubt No. 5 at the end

of our position’s left flank. In front of the redoubt was a

lodgement which was always—day and night—occupied by our picquet

line. Officers rotated daily duty in the lodgements. This redoubt was

located far from the position and the jägers there were completely

on their own—there was not even the enemy facing them. Bands of

Turks that rarely appeared quickly slipped away thanks to our